The following is my contribution to the fabulous Pre-Code Blogathon, hosted by Shadows and Satin and Pre-Code.com. murder at the vanities

A word, or two or three, about Pre-Code Pictures

Even if you’ve seen some of the now-classic pre-code films, like “Night Nurse” (1931), “Freaks” (1932), or “I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang” (1932), it can be hard to imagine the sheer volume of skin, moral turpitude, and—every so often—political or social reality that filled the pre-code films of Hollywood. In the more famous films, much of the “pre-code” material was used in the service of a good story or genuinely interesting characters. In lots and lots of other pre-code films, however, the material cultural conservatives found objectionable was simply tossed into a blender with a couple of nouns and a verb or two, and voilà! a quick and often tidy profit.

The guiding principle of the code was “No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it,” which is predictably squishy. What the writers of the Code meant was— “Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.” This is unfortunate, since much great art is almost exclusively the ridicule of human laws, and the great art that isn’t, is probably based on sympathy for the “violation” of such laws. Oh well.

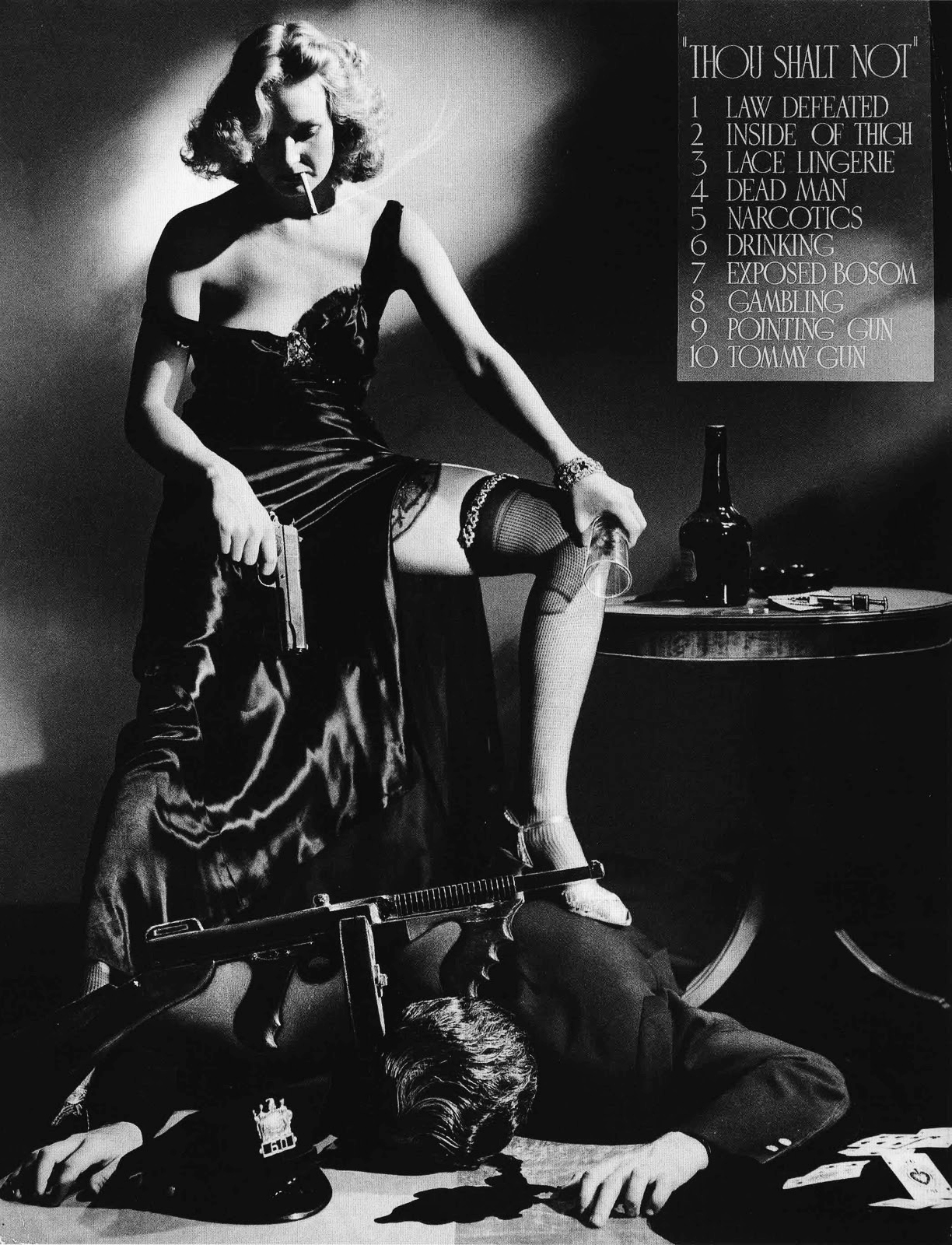

There’s much too much in the code to mention it all, but let’s review what became the more striking unmentionables and invisibles: murder, the explicit presentation of “methods of crime” (including but not limited to theft, robbery, safe-cracking, dynamiting of trains, mines, or buildings, arson, the use of firearms, and smuggling), illegal drug traffic, the use of liquor, explicitly or attractively presented adultery, sex perversion (the classy way to refer to plots with characters who might possibly be thought, even for the most fleeting of moments, to be gay), white slavery, miscegenation, and venereal diseases. Oh, and seduction is “never the proper subject for comedy.”

There were predictably silly rules about costume, dancing, national feelings, locations (apparently “location” actually means “bedroom”—it’s the only one mentioned), and surgical operations. A fairly well-known convention of the Code was that crime and villains were never to be portrayed sympathetically. It was absolutely verboten that a criminal of any sort be allowed to get away with anything. The theory was that, as long as the crime (and sex) was punished in the end, nobody would get any funny ideas. (Clearly, there were people making pictures who knew better, but you have to wonder—didn’t everybody know better?)

I mention all this because short of surgery and the dynamiting of trains, all of those no-nos seem to have been stuffed into the very rickety “plot” of “Murder at the Vanities.” It’s a ridiculous movie but totally worth seeing to get a sense of the generally cheerful lunacy that seems to guide a lot of pre-code films. “Murder at the Vanities” is a clown car of bat-shittery, with one misbegotten scenario after another tumbling out.

I’m not sure a set-up is required to understand what follows, but here it is: This is a film about a (real) Broadway show, Earl Carroll’s Vanities, with—three guesses, no peeking—a murder mystery slapped on top of the endless parade of chorines. (I love that word, chorine.) One of the virtues of setting your plot in a Broadway revue is that you can string together a series of musical numbers that bear absolutely no relation to each other or to the plot, and nobody bats an eye. A European star, Eric Lander (Carl Brisson) and his leading chorine (see?), singer Ann Ware (Kitty Carlisle) are all set to perform at the opening night of the Vanities, and get married immediately afterward. As they swan off to the theater, Ann laughs, “This is the happiest night of my life, Eric, and nothing, nothing can spoil it!” Now that we know Ann’s night will absolutely be spoiled, and spoiled in some unforseeably awful way, the film wastes no time diving into the splendidly tawdry backstage shenanigans.

Problem one: Lander previously romanced another woman in the show, Rita Ross (Gertrude Michael), and she is having none of this marrying-Ann business. Michael’s portrayal of villainess Rita is admirably enthusiastic.t49O

Problem two: Lander’s mother (Jessie Ralph), incognito as a wardrobe assistant, is on the run from a murder she committed in Vienna thirty years ago. This youthful indiscretion is batted aside as an airy nothing. To wit: it was thirty years ago, she has suffered, and anyway he was a bad guy. It took me a minute to figure out that the woman who introduces this background into the plot is a professional private detective. There is no jokey introduction of her or her profession to help the audience get past the fact that she’s got lady-parts and is simultaneously a detective whom people pay to do a job. She’s just there and that’s what she does for a living, and it’s awesome. Cue the bizarre musical number in which Lander is dressed as though he’s been shipwrecked, with nearly naked women strewn “artistically” about the stage.

Shortly after this, the bodies start dropping, and not a moment too soon. I have not yet been converted to the style of singing popular in such revues, so the dead bodies were a welcome diversion.

But the next musical number had the Husband and me suddenly sitting up a little straighter. Rita is singing, appropriately enough, about a lost love. The first thing that caught me off guard is the truly awful gown they’ve got her wearing. Perhaps the wardrobe department already has it in for her. There’s a line of sombrero-hatted fellas with guitars backing her up. What got our attention is that naughty Rita’s Mexican-flavoured song is an ode to marijuana.

Soothe me with your caress

Sweet marijuana, marijuaaaana

Help me in my distress

Sweet marijuana, please do

The racism inherent in the it’s-about-marijuana-so-obviously-the-number-has-to-be-Mexican is par for the course. And it is the villain serenading her jazz cigarettes, after all. None of this really undercuts the effect, at least not now, in 2015.

You alone can bring my lover to back to me

Even though I know it’s all a fantasy

And then put me to sleep

Sweet marijuana, marijuana

Okey dokey then.

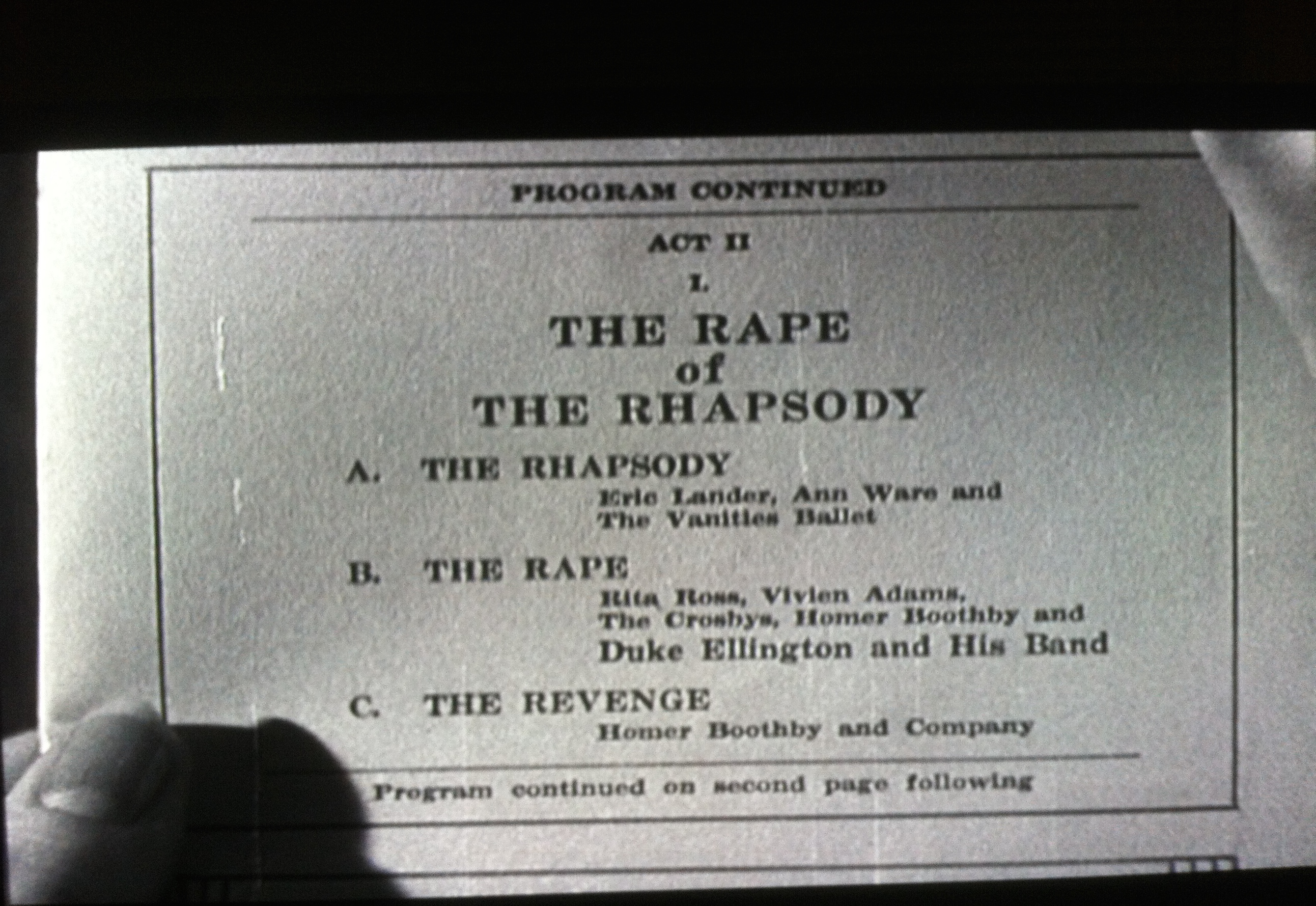

This is all merely the prelude to the centerpiece of weirdness, aka the Vanities‘ Act II.

This isn’t helping.

Yes, folks, “The Rape of the Rhapsody,” the rhapsody being sung by Lander and Ware, both in proto-Liberace outfits more ridiculous than you could have imagined possible, and the rape, as you can see above, courtesy of Rita, Duke Ellington and His Band, and a bevy of African-American chorines. It’s hard to do justice, if that’s the right word, to either the spectacle or the subtext.

The general idea, I presume, is that the hot new jazz music is violating the elegant classical music. Of course, it’s not just the metaphor of rape that’s icky, but the way the number is racialized. You’re probably wondering—might it be somehow less offensive if there’s a white lady in a sexualized mammy outfit singing “Ebony Rhapsody” in front of a line of black chorines in sexy French maid outfits? Let me assure you, it is not. The only thing that keeps me from saying it’s worse is that it’s just so…weird.

Ellington is, of course, a joy to watch, and his band wipe the floor with the “rhapsody” musicians.

If this fruitcake number is the musical climax of Murder at the Vanities, then the revelation of one of the murderers in the last ten minutes of the film is the dramatic climax. Spoilers ahead. In a blow for labor rights, Rita’s put-upon maid has shot Rita in the back. You can hardly blame Norma (Dorothy Stickney). Working for Rita is better than working at Wal-Mart, but not by much. Stickney’s wild-eyed confession is something to see. She only confesses to keep Lander, with whom she is smitten, from being arrested for the crime.

If you want to be surprised when you watch the movie, STOP READING NOW. Because this is one of the most enjoyable moments in the film, I wanted to share it with you, and it’s my blog, so here goes:

Norma begins where other, lesser murderesses would be wrapping up. “Oh, I’d’ve told alright. Rita deserved to go to the chair. She was rotten to everybody. I’m glad she’s dead!”

[The clip won’t start at the right place, so forward it to 39:47, and enjoy.]

I hereby nominate Ms. Stickney for Best Pre-Code Murder Confession.

I’m looking forward to watching more of the less famous pre-codes, discovering some old gems, and some more of these time-capsules of aesthetic lunacy. If you enjoyed this, please check out the other posts in the Pre-Code Blogathon at Pre-Code.com and Satin and Shadows!

Please nominate more Best Murder Confessions in the comments, Pre-Code, or otherwise!

For some other takes on “Murder at the Vanities,” see the Nitrate Diva and Pre-Code.com. I had exactly the same reaction to Carl Brisson as the Diva did: Where is Maurice Chevalier when you need him?!